In May 2019, Teshome, a farmer in Kobo, sowed his sorghum seeds. May is the typical time to do this according to the local crop calendar. Kobo is a woreda (or district) in the Amhara region of northern Ethiopia where sorghum is one of the staple crops. It is typically a rain-fed crop in this region, meaning its successful growth and harvesting rely on the climate and weather.

That year, the rain did not come as expected, and by the time the November harvesting period arrived, no sorghum had grown for Teshome and many other farmers in Kobo. His irrigated crops were still thriving thanks to reliable watering and routine extension services he received to help him improve his agricultural techniques and maximize his harvest. However, the loss of his rain-fed crops would be heavily felt as they normally provided an important additional source of both food and income for his household. The low rainfall levels simulated drought-like conditions, resulting in a payout of ETB 2,000 (or about US$57) due to the insurance he had purchased. Though not a huge sum of money, he was able to use this to purchase food for his family and other essential household items at the local market.

Teshome’s story illustrates the importance and power of being able to bounce back, or have greater resilience, after a climate event happens. Approximately 950 farming households in Kobo experienced this drought in 2019, but only three had insured their crops. In Ethiopia, such farmers would have to cope with their losses by reducing household consumption (e.g., eating less, buying less clothing, buying less kerosene oil for lighting, etc.), borrowing at high rates, selling valuable assets such as livestock, or relying on monetary gifts from family members.

Climate change and low-income populations

Ethiopia is a country prone to many climate risks, which particularly affect its majority rural population (80% of its 110 million plus population live in rural areas), like the sorghum farmer from Kobo. This matters because climate change, most notably drought and altered rain patterns, continues to pose challenges for rural Ethiopians’ livelihoods and rain-fed crop production. To manage these agriculture-related climate risks, Ethiopian farmers turn to informal coping mechanisms such as spending down the little savings they may have, selling valuable assets at heavy discounts, and reducing consumption (which often means going hungry). Very rarely has insurance been an option; until recently, insurers in Ethiopia had almost no footprint in rural areas with smallholder farmers. In fact, 2014 data shows less than 2% of Ethiopians were covered by any type of formal microinsurance1 product.

Not only a problem in Ethiopia, climate change disproportionately affects low-income and vulnerable populations around the world, which could lead to an additional 100 million people living in extreme poverty by 2030. Because insurance is an ex-post tool (only helping after the unfortunate risk event occurs), and not all risks are insurable, a holistic approach to dealing with climate risks – one that includes but is not limited to insurance - is needed to help vulnerable communities become more resilient.

Here we present an example of a holistic risk management solution that the MicroInsurance Centre at Milliman2 developed for smallholder farmers in northern Ethiopia. The product illustrates Milliman’s Climate Resilience Initiative’s (MCRI) holistic approach to enhancing climate resilience in low-income communities.

One journey to developing a holistic risk management solution

Teshome, the sorghum farmer from the opening story, is part of an innovative risk management pilot project in which Kobo is one of the community sites. In 2017, the MicroInsurance Centre at Milliman (MIC@M) began exploring climate risks in rural Ethiopia with the end goal of developing a formal risk management solution for smallholder farmers. This was part of the UN’s International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) grant-funded project “Managing risks for rural development: Promoting microinsurance innovations” (MRRD) being implemented by the MIC@M. (To learn more about the project, read the Project Fast Facts flyer).

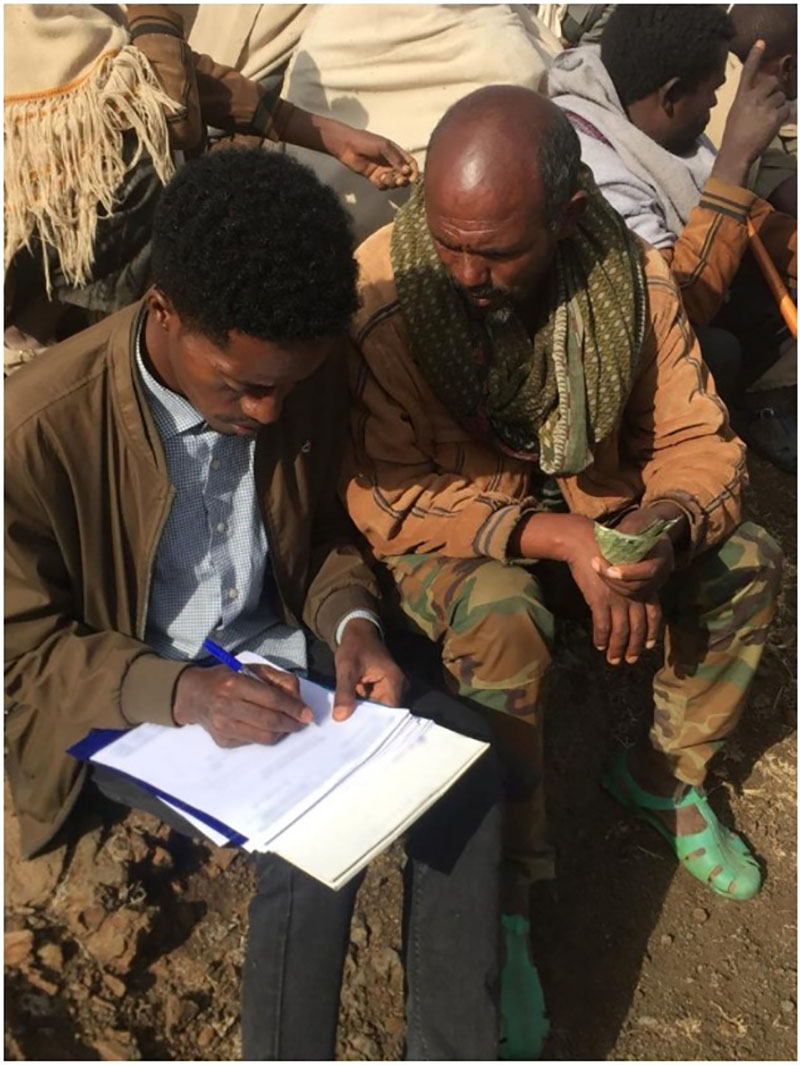

A cereals farmer in Tigray enrolling in the index insurance product to protect his crops against drought

The MIC@M began by performing a country-level assessment of microinsurance supply, demand, distribution, regulatory context, and IFAD programming in Ethiopia. The team took into consideration that not all risks and not all rural households are insurable. Based on the results, the MIC@M team developed agricultural index insurance linked to other services to help reduce some production risks faced by smallholders. It has been piloted in six communities in the Tigray and Amhara regions.

The end goal of this solution is ultimately to enhance the climate resilience of households, providing them the necessary financial and practical tools to manage their risks and bounce back more quickly when a drought occurs.

What does this solution look like in the real world? Farmers enroll through their local Irrigation Water Users’ Association (IWUA) or local Rural Savings and Credit Cooperative (RuSACCO). They voluntarily purchase the microinsurance product, which is an index (or parametric) insurance product that automatically pays them if a certain level of rainfall and vegetation health are not reached in their geographical area during the growing season. That is, no “proof” is required of their crop losses; the rainfall is assessed via satellite data and compared to normal year records to assess potential crop losses. Essentially, they are protecting themselves and their families against the financial effects of drought.

In order to fulfill the holistic approach to risk management, the MIC@M team facilitated a link between the insurance and agricultural extension services – support for farmers to improve their agricultural techniques and practices in order to reduce the impact of the climate risks or to address related risks not covered by the insurance.

Entering into the “right” partnerships to develop and deliver microinsurance and other risk management solutions to low-income clients is arguably the most crucial factor of success from the supply-side aspect. Because the solutions are multifaceted, it is important to have partners with specialties in specific areas, such as insurance, index design, agriculture, and other appropriate risk management services. Multiple partners are typically also needed in order to reach low-income people where they are and to simplify processes and build trust from the client perspective.

The implementation of the MRRD project’s holistic risk management solution relies on a network of partnerships, including Ethiopian insurers and a multinational reinsurer that underwrite the risk, agricultural expert agents that provide the technical support on farming practices, and distribution channels that are trusted and accessible to the target low-income communities (i.e., IWUAs and RuSACCOs mentioned above). For the Ethiopian insurers involved in this project, this opened up a new rural market opportunity for them with virtually untapped demand for these risk management solutions.

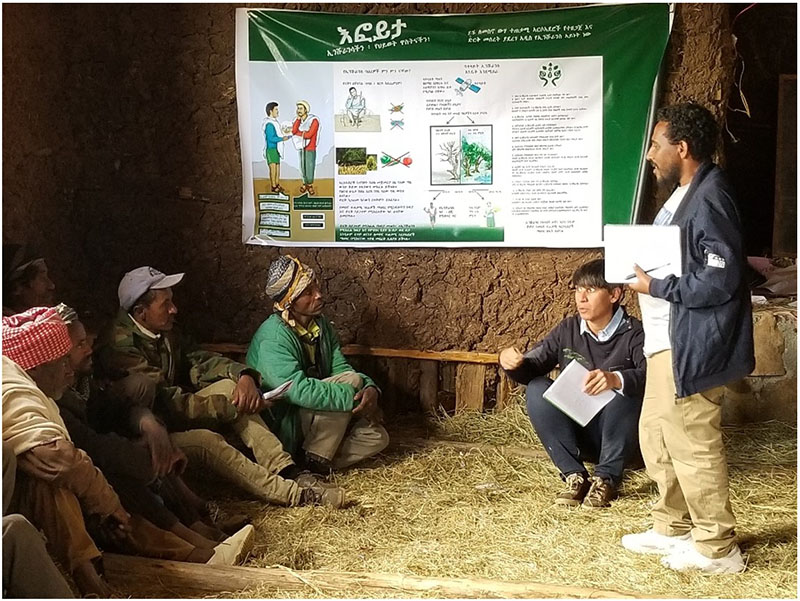

The MIC@M Ethiopia team meeting with farmer members of the Irrigation Water Users' Association (IWUA) to explain the features of the index insurance product and answer questions.

Increasing climate resilience beyond Ethiopia

The MRRD project in Ethiopia is just one example of using holistic risk management to increase climate resilience of low-income households. There are several global examples from different geographies and employing different tools, engaging both public and private sector.

Demonstrating this collective action to increase climate resilience and realize untapped market opportunities is the InsuResilience Global Partnership for Climate and Disaster Risk Finance and Insurance Solutions (The Partnership), of which the MIC@M is a member. The Partnership was launched in 2017 with the goal of bringing together country governments, the private sector, civil society, international organizations, and academia to increase resilience among the most poor and vulnerable people. Among their private sector members are some of the global leaders in insurance and reinsurance, understanding both the urgency of climate change and the growth and market opportunities that exist in providing climate resilience solutions.

Helping to make the world’s most vulnerable populations resilient to climate risks involves significant innovation in risk management approaches, and a diverse group of organizations willing to develop, implement, and manage these solutions in a way that creates value for all parties.

1Microinsurance can be defined as “risk-pooling products that are designed to be appropriate for the low-income market in relation to cost, terms, coverage, and delivery mechanisms.”

2The MicroInsurance Centre at Milliman (MIC@M) is a specialized practice within Milliman dedicated to generating access to risk management solutions for 3 billion low-income people globally.